Allhallows Defences & The Battle of Britain

German reconnaissance photo of Allhallows taken May/June 1940. Photo: Nigel J Clarke Publications, by kind permission. Captions added by Mitch Peeke.

June 1940: as German forces had now rolled up Europe and pushed the beleaguered British back home from Dunkirk, the defence of the British Isles became a paramount concern. The country’s coastal defences were strengthened, with many miles of barbed wire springing up. Some beaches were closed and land-mined whilst others had signs erected warning of mines that were not actually present.

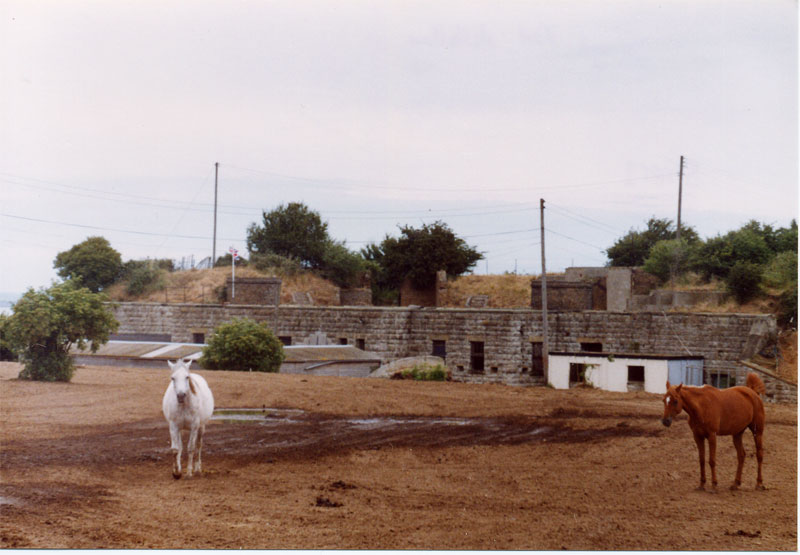

Other residual defences from the Napoleonic era were brought into play at this crucial time too. Built in 1867, Slough Fort at Allhallows, which still stands today on the Kent side of the Thames estuary, is a fine example of this.

In late 1939, the British army had again requisitioned the old fort as part of the coastal defence programme. There were four coastal defence guns sited facing north, utilising the first world war extensions that were built onto the fort’s original wing batteries, where in 1914, a pair of 6-inch quick firing guns and a pair of heavy 9.2-inch breech-loaders had once stood. In May of 1940, the men of 159 battery, 53 (city of London) heavy anti-aircraft regiment of the Royal Artillery also moved in, though their four modern 4.5-inch, quick firing guns were positioned about a quarter of a mile away from the fort in what is now Avery way, on a purpose built emplacement facing east.

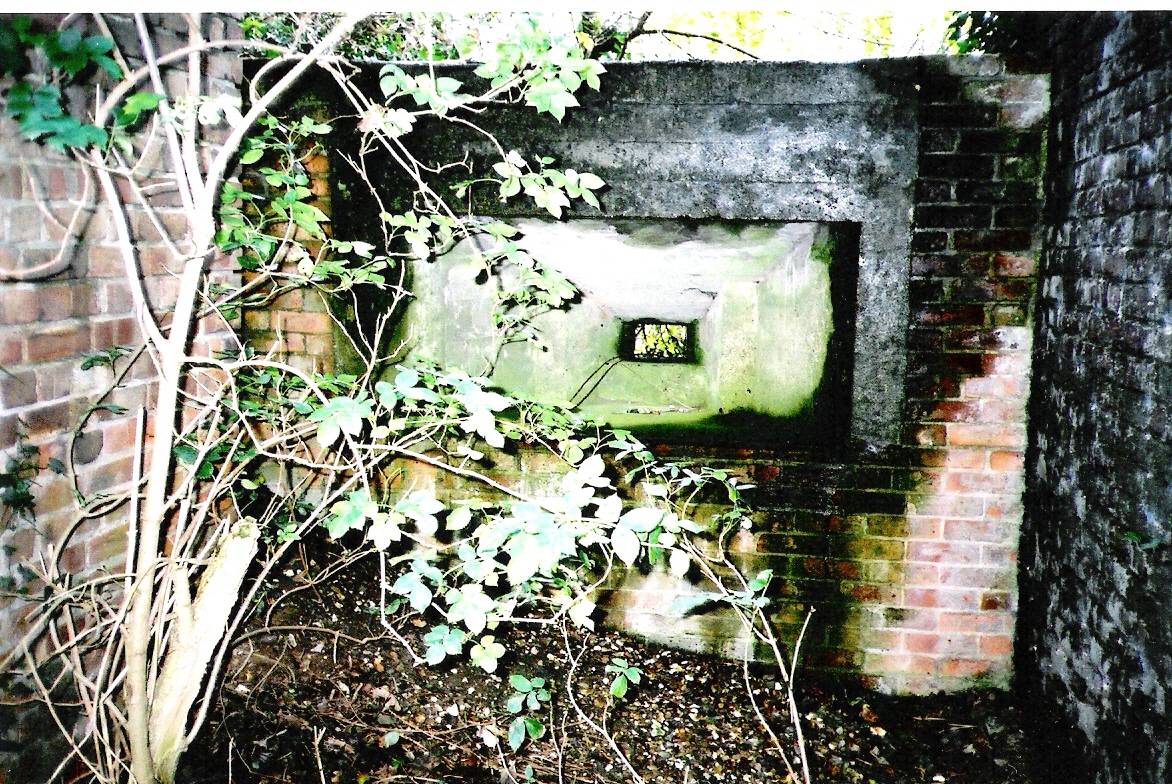

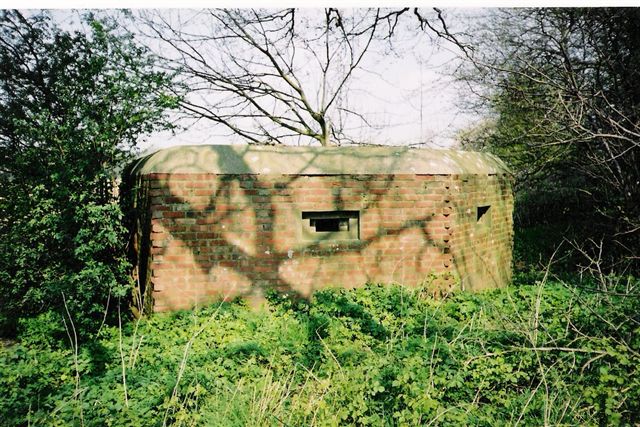

Furthermore, a chain of ten “type 24” concrete pillboxes, each capable of holding eight soldiers, was also constructed from the western side of the fort extending across farmland toward St Mary Hoo, as a subsidiary defence line to prevent enemy landings on the sands. Of these ten pillboxes, seven remain today, though only six of them can be seen from public footpaths. The seventh surviving box is now inside the confines of a private garden.

A line of large stone blocks and wooden staves supporting barbed wire entanglements was laid at the low water mark of the west beach and long, angular, iron obstructions supporting scaffold poles; some of which still surface periodically and have to be removed, were emplaced on the main Allhallows beach.

Allhallows was also home to observer corps post 1/bravo 1; a unique emplacement in that it was situated in the village’s coast guard cottage, atop a rise in the land at the junction of what is now home wards road and Ratcliffe highway. The location had been chosen for its commanding view of both the Thames and Medway estuaries.

Although it has always been a little known seaside resort, then situated at the end of the southern railway’s branch line from Gravesend and seemingly at the end of the road from the middle of nowhere, Allhallows was very much a place of strategic importance in the summer of 1940, as indeed was the rest of the Hoo Peninsula, and the fact that the Luftwaffe photographed the village and correspondingly prepared a target information sheet on Allhallows, shows the degree of importance they evidently attached to the place, too.

On 5th September at 15:10 hours, the Luftwaffe was over the Hoo Peninsula again. 166 battery 53 (city of London) heavy anti-aircraft regiment, observed twelve Heinkels north of their site, position s9, near Chattenden, Rochester; flying east at an estimated height of 19,000 ft but sadly out of the range of their guns. The Thames Haven oil storage tanks on the Essex bank of the Thames, always a good target, were the bombers’ objective.

Their counterparts of 159 battery based at Allhallows, logged that at 15:12 hours their four 4.5 inch guns engaged the same twelve Heinkels north-west of their position. Upon engagement by 159 battery, the raiders quickly climbed from 17,500 feet to 21,000 in an attempt to avoid the intense barrage being put up by the Essex gunners as well as those at Allhallows. However, the twelve German bombers made only a fleeting attack and were soon clear of Thames Haven and on their way home.

At about 18:00 hrs, the Luftwaffe decided to carry out an attack specifically aimed at Thames Haven, though at a lower altitude than the previous, secondary attack. Once again, the Essex anti-aircraft sites and 159 battery at Allhallows engaged these other raiders, the gunners putting up a fearsome barrage of high explosive at the enemy, with notable effect. This time, the anti-aircraft gunners shot down two German aircraft, both Heinkel HE111s from iii/KG53.

The first of the two, hit by the heavy concentration of anti-aircraft fire from the Essex batteries over Thames Haven, subsequently crashed into the sea off Herne Bay, killing all five of its crew. The second bomber, possibly already damaged over Thames Haven, had dropped out of the main formation immediately on leaving the target area and subsequently flew directly along the south side of the Thames in an attempt to avoid the deadly fusillades from the Essex batteries.

Unfortunately for Feldwebel Anger and his crew, their attempted evasive action also took them directly over the coastal defence position of Slough Fort and just to the left of 159 heavy anti-aircraft battery at Allhallows. The gunners of both positions fervently added to the discomfort of the already distressed bombers crew, with their own combination of small arms fire and 4.5-inch high explosive shells.

With his badly hit aircraft now streaming black smoke and rapidly losing height amid the hail of shell and small arms fire that was ceaselessly aimed at him, Anger was forced to ditch the stricken bomber in the relatively shallow water off the Nore, by the Medway Estuary. Only two of Feldwebel Anger’s crew survived the Heinkels watery crash-landing. Feldwebel Waier and Unteroffizier Lenger were picked up by a Royal Navy patrol boat and taken prisoner. Feldwebel Anger, Unteroffizier Armbruster and Gefreiter Novotny were all killed.

As the remaining bombers headed home, the men of the fire brigade arrived to tackle the blaze at Thames Haven. They had a full night’s work ahead of them.. A direct hit by one of KG53’s bombs on a tank containing 5,000 gallons of lubricating oil, sent a thick pall of smoke into the sky, reminding all for miles around of Dunkirk again, but the Essex and Allhallows ack-ack gunners had struck back at the enemy. The wreck of Feldwebel Anger’s shattered Heinkel 111 was subsequently removed as it was considered to be a hazard to navigation.

On Sunday 7th September, another element of the Allhallows defences played a crucial part in the day’s events. The day started much like any other thus far for the tired pilots of RAF fighter command, except that the German formations were markedly later than usual in coming. This was due to the fact that Reichs Marschall goring himself was coming to direct the day’s operations personally.

On the British side of the channel, the RDF stations soon started plotting the incoming raiders. The RAF fighter squadrons were scrambled and ordered to their usual patrol lines, at their usual altitudes in readiness to defend once more their precious bases, the Luftwaffe’s usual targets. But today was about to prove different.

When the defending RAF fighters reached their interception points, they could find no trace of the expected German formations. The sky appeared remarkably empty, yet the plotting tables showed that massed formations of enemy aircraft had crossed the English coast. The raiders, more by luck than judgement, had unintentionally slipped past the waiting fighters and then altered course around them, splitting into two distinct formations as they headed toward their real objective.

Fortunately, observer post 1/bravo 1 at Allhallows had a grandstand view of the approaching German formations and with other observer posts in the network, they quickly alerted their headquarters at Maidstone, who in turn directly alerted fighter command as to the raiders actual position and their change of course. On September 7th, the aerial armada of German bombers was ignoring the RAF fighter stations and for the first time, the German bombers were heading straight for London.

The story of the Battle of Britain needs no recounting here, but the remains of the anti-invasion infrastructure are still wonderfully intact at Allhallows, and if one is armed with the story behind them, they become all the more poignant when you stand beside them. I am very fortunate in this respect because i live here and walk my dogs along the defence line almost every day. I took the pictures accompanying this article over the course of many such dog walks. I hope you enjoy them. The text was largely excerpted from my latest book A Summer of Swallows and Merlins, which I am currently writing. I will keep you posted on its progress.

And Finally…………………

I’ve put this one in purely for your interest, as it is not related to the article. Boxcliffe. Type 24 Pillbox at Cliffe. One of a pair standing beside the B2000. Note the brick shuttering still in place.